Where do our muscle tear scanning intervals come from? (AKA our promise)

Posterior Calf Long

Anterior Calf Deep

Posterior Calf Axial

Anterior Calf Deep

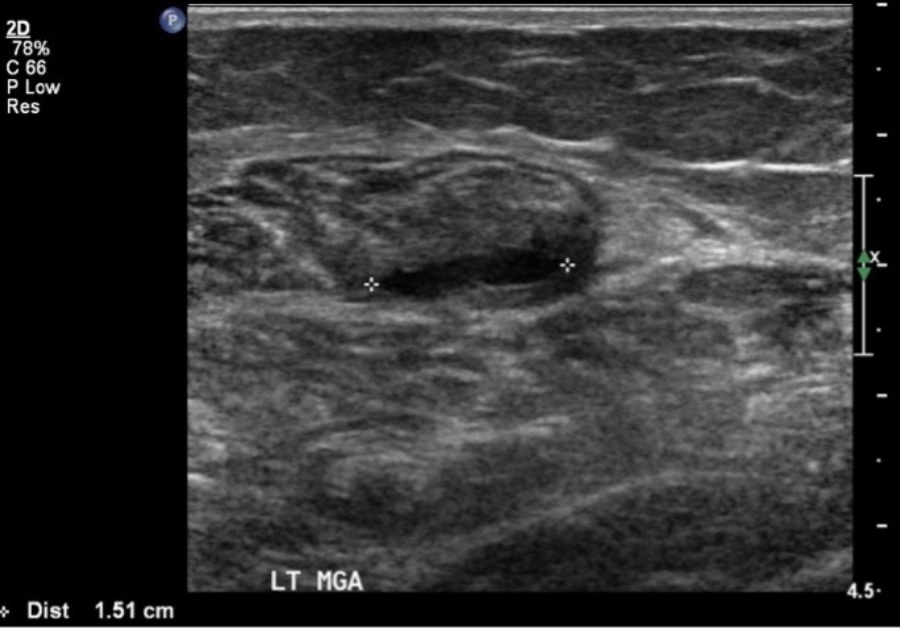

Long and axial views of a medial gastrocnemius muscle tear. Arrow = fluid filling the tear

Scott Allen recently talked about our current thinking (yes, it may well change) regarding muscle tears. He mentioned three key points:

1. examine 48hrs, follow-up 7-10 days & further follow-up determined by findings and patient specific factors

2. how imaging effects management, mainly involved with acquiring a patient specific diagnosis, and one factor in return to play consideration

3. not grading muscle tears, but describing structures, extent and associated factors, such as haemorrhage.

We thought it might be sensible to add a little insight into how we arrived at the intervals and ultrasound tear evaluation.

Most readers may remember sitting in a physiology class at some point, blinking while endless slides scrolled past, showing pictures of tissue samples, cartoon diagrams of histological responses, and graphs showing wobbly healing curves. Tissue healing has its own ideal timeframe and environment to allow for a best case scenario for injury healing. This has been thoroughly established, adequately or even well taught, and sometimes painfully examined at the end of the university course/paper. The point is, we have a clear idea of what to expect when a muscle injury is healing (see associated table for some references).

Of course, we acknowledge that this clear idea is all very well on paper or in a laboratory environment. The reality will certainly be different for each injury, based on the individual patient factors, and even how these factors change and influence each other.1

This individuality will require careful consideration of both timing of intervention, as well as the specific of that intervention. We think that having as clear as possible a picture of the specifics of the injury, its resolution or progression, its response to loading or unloading, will help focus this consideration.

Carles Pedret, a sonologist working with elite footballers in Spain, and author of “Ultrasound classification of medial gastrocnemius injuries”2 recently published a video 3 in which he discusses muscle tear reinjury, and the likely contributing factors. He looks at game time loss, noting that reinjury is potentially more a problem than the initial injury. He describes the anatomical changes associated with injury, and how they each may predispose reinjury. He also notes that returning to play too early, or iatrogenic factors, are potential reinjury risks.

Ignoring the ability to direct management more specifically based on objective signs of tissue healing, we think falls into this category of risks. The table above gives a simplified version of tissue healing steps, and what we would look for at each. We hope that by being specific about not only tissue changes but also the factors measurable with ultrasound at each stage, that those who are managing acute injury will agree that, because it is possible to look for this detail, that such detail must form part of clinical reasoning during muscle tear rehabilitation. Failing to utilise such powerful information risks returning people to play too early, and we could reasonably accuse ourselves of inviting iatrogenic injury.

We realise this is a strong opinion, and as such must include a voice of reason. It is possible that we are wrong, that such objective information either won’t improve return to play times, won’t decrease reinjury, or won’t meaningfully affect clinical outcomes. Our call to action, is the need to establish whether it really makes a difference. Our promise is that we will carefully produce a framework to collect and evaluate data, an internal audit if you like, that seeks to establish how injury specifics, such as those described in the table , effect return to play times and other prognostic factors. Practically speaking, we realise that by telling you your patients should be scanned within 48 hours, that we need to make that happen for you. We will.

*NB. This is version 0.2 or so of this table. It may be more wrong than right. It probably is. Work with us to get to version 1.0.

References:

Meeuwisse W, Tyreman H, Hagel B, Emery C. A dynamic model of etiology in sport injury: the recursive nature of risk and causation. Clin J Sport Med [Internet]. 2007 May [cited 2021 Sep 29];17(3):215–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17513916/

Pedret C, Balius R, Blasi M, Dávila F, Aramendi JF, Masci L, et al. Ultrasound classification of medial gastrocnemious injuries. Scand J Med Sci Sports [Internet]. 2020 Dec 1 [cited 2021 Sep 29];30(12):2456–65. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/sms.13812

Why do we suffer reinjuries after a muscle injury? - YouTube [Internet]. [cited 2021 Sep 29]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_gva5HEDvV8