Our grading system is based on anatomy, not numbers.

Serial ultrasound examination of a quadriceps muscle injury. Our grading system is based on anatomy, not numbers.

A 61-year-old man presented suffering from right anterior thigh pain following tripping and essentially doing the splits. He described it as being very painful initially, then decreasing in discomfort since to the extent he had been able to do some light loading.

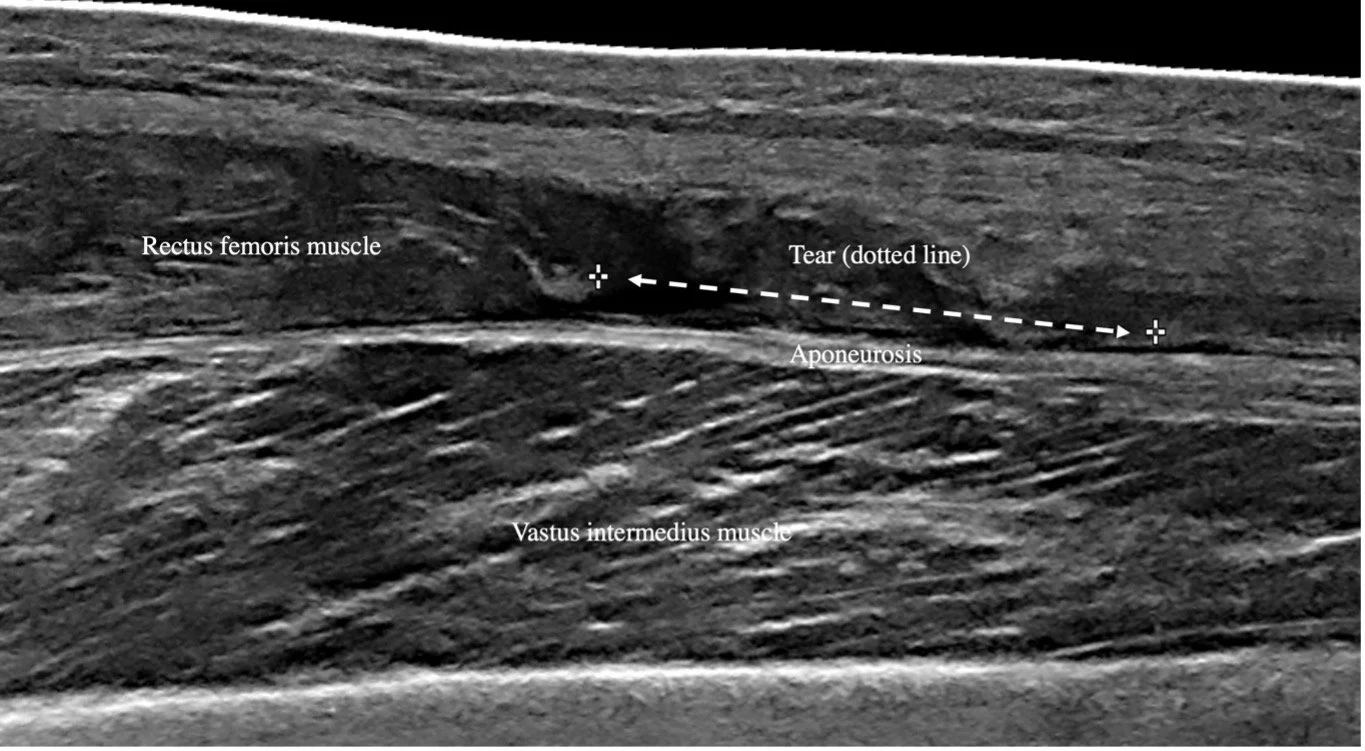

Ultrasound examination (Philips Affiniti70, eL18-4 MHz PureWave transducer) of his right quadriceps muscles was performed. The examination demonstrated a “Rectus femoris musculotendinous junction muscle tear, with associated haematoma.”

Key findings (Image A) included “The rectus femoris distal musculotendinous junction has a tear (51 x 9mm), with muscle fibre relaxation, and associated fluid (51 x 16 x 5mm = 2.1ml).”. Ten days later, the patient returned for follow-up examination. The examination indicated “

Rectus femoris musculotendinous junction tear without appropriate activation movement is consistent with a complete tear of the aponeurosis. Reduction in haematoma size.”. Key findings (Image B) included “The rectus femoris distal muscle has “bull nosing”, a fluid-filled gap (20mm length x 10 mm axial x 4mm deep = 0.4ml), and adjacent thickened retracted rectus femoris tendon part of the quadriceps tendon. Activating rectus femoris muscle shows thickening without appropriate movement.”.

A.

B.

Figure 1:Ultrasound images of the right quadriceps.

A shows the initial examination of the rectus femoris distal musculotendinous junction in long view, tear indicated by hashmarks and dotted arrow.

B shows the second examination the of rectus femoris distal musculotendinous junction in long view, tear indicated by hashmarks and dotted arrow

The first point to make about the two ultrasound examinations is that the injury diagnosis became more detailed from the first to the second examination. Our experience has been that a ‘one and done’ approach to diagnosis is less accurate than serial examinations. Firstly, it can be difficult to fully appreciate the injury early, especially if it is either subtle or complex. We have talked before (see here and here) about the importance of early ultrasound examination to help guide injury ‘first aid’. Perhaps equally importantly, one time point neither captures the evolution of the injury, nor does it account for the patient as an individual within their own specific circumstances. An injury may be worsened over time despite the best management and adherence to advice. Hall1 describes the role of ultrasound evaluation of thigh muscle injury, stating that a key advantage of ultrasound over other tools, is the ability to provide serial examinations as a guide to rehabilitation and return to play decision making. Hamilton et al.,2 echo this sentiment, suggesting it to be counterintuitive that a single time point can account for factors that may occur several weeks or longer into the future.

The second point to outline is that we are reporting muscle tears using a patient-specific injury classification system. For some time, we have been aware that the breadth of grading systems between and within injury locations was not only difficult to remember but also failed to account for anatomical and injury-specific factors. For example, should a two-joint muscle tear of the same characteristics as a one-joint muscle injury be graded in the same way?

Hamilton makes the point that the diverse grading systems do not facilitate clear return to play times nor accurate injury management and that:

“…a uniform classification system for muscle injuries must be a priority for sports medicine; its approach should be targeted to facilitating optimal management strategies rather than attempting to predict RTP durations. The clear description of anatomy and pathology through careful history, examination, and appropriate imaging will facilitate an accurate management strategy for every injury. In addition, we propose that careful serial clinical assessments and shared decision making in the process of RTP will move us closer to our target of an accurate prediction for time to RTP”. 2

Our interpretation of this has led to a grading-free classification system comprised seven factors:

Tear or no tear

Size of tear

Structure(s) torn

Site of tear

Haemorrhage

Muscle dynamic contraction

Vascularity at tear site

We appreciate that this only accounts for the biomechanical properties of injury and does not factor psychosocial variables, which clearly impact recovery from injury and return to activity. However, we believe that being entirely injury-specific across the duration of the injury is the best way for us to add value to the complex clinical rehabilitation picture.

References:

Hall M. Return to Play After Thigh Muscle Injury: Utility of Serial Ultrasound in Guiding Clinical Progression. Curr Sports Med Rep [Internet]. 2018 Sep 1;17(9):296–301. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30204633/

Hamilton B, Alonso J, Best T. Time for a Paradigm Shift in the Classification of Muscle Injuries]. J Sport HEalthSci 2017.